Published Work

Teesdale Mercury (Barnard Castle, County Durham)

Autumn/Winter 2012

A Nation Displaced - The Spread of Scottish Culture

Published in 'Scottish Field' July 2012

Stand amidst the splendour of the annual Edinburgh military tattoo set against the backdrop of Edinburgh Castle and listen to the announcements of the various pipe bands. Each year representatives from the Commonwealth, notably Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand grace the esplanade, giving credence to the adage that Scots populated the empire taking their traditions with them. These are hardly revelations, nor are the pipe bands from the United States with a strong Scots connection. However a chance encounter in the mountains of the Highlands caused me to consider the wider influence of Scottish traditions and culture…

Returning from the peak of Sgurr Thulim above the iconic Glenfinnan viaduct, so often seen in film, the gentle skirl of the pipes was heard drifting up from the side of Loch Shiel not too far distant. Seemingly like a magnet I found myself drawn to it, the familiar tunes echoing around the surrounding hillsides and stirring the spirits within.

At the monument erected in 1815 to mark the place where Bonnie Prince Charlie raised his standard, at the beginning of the 1745 Jacobite Rising, I found a tall man wearing jeans and an open-necked casual shirt playing the bagpipes with an enthusiasm that was infectious. As he finished a stirring rendition of ‘Bonnie Black Isle’ I congratulated him and said how his playing had drawn me down from the hills. To my surprise his accent did not portray the expected Scottish brogue but was distinctly Teutonic in tone. Further enquiry revealed he was from Munich and had come to Scotland as a pilgrimage, part of which was to play the pipes in this scenic location. He had involvement with an organisation called Schotten Radio and began to detail the ‘Scottishness’ that had taken hold within Germany. It was revelation to discover that perhaps one of the most familiar and uplifting bagpipe tunes of recent years, namely ‘Highland Cathedral’, was actually written by a pair of Germans!

Intrigue and curiosity drew me to Germany and I found myself in a familiar world in an alien land. The first weekend in May sees the Annual Highland Gathering at Peine, near Hannover, where 20,000 fans of Scottish culture and traditions gather.

Surrounded by stereotypical German architecture, all spotlessly clean and well ordered I wandered past the Rathaus on the Marktplatz and down to the Stadtpark via the Jakobi Kirche. Everything around me shouted Germany until the feint skirl of massed pipes was heard. The sight and sound of the pipes transported me back to those on the esplanade of Edinburgh castle. The bands gathered in the market place and marched through the streets in a surreal swirl of tartan and saltires. Elsewhere, ‘Scottish pursuits’ were clearing substantial holes in the crowd. Here, cabers were being tossed, stones putted and the Tug a wa´ was central to a crowd that ebbed and flowed like a tidal surge as first one, then the other team dominated the pull. Whisky tasting booths, Highland dancers and even an enterprising outfit that was taking orders on made to measure kilts… I was in Germany but all was Scottish bar the language!

Where had these connections stemmed from?

My mind immediately went to the German connection with our Royal Family and notably the influence of Prince Albert who had so fallen in love with this landscape and culture along with his wife, Victoria. Also the composer Felix Mendelsohn had famously written his Hebridean overture that brings to life famous landmarks such as Fingal’s Cave on the small island of Staffa. Further research led me to the connections many centuries before with the establishment of the Hanseatic League trading links back in the 13th to the 17th centuries. These links still exist with approximately 18, 000 Germans living and working in Scotland today.

The answer was obvious… Post World War Two the British Army on the Rhine had been based here.

Chatting with the President of The Scottish Culture Club, Ernst August Horneffer, all fell into place. The 42nd Highlanders had been posted in the area and some of the locals had taken to the sound of the pipes, been taught by the soldiers and so the festival had begun. They had even travelled to Cowal and other Highland Games for further inspiration. As a marketing ploy for this small regional town it has worked. Seventeen Pipe Bands were competing here, mainly from Germany, but some from The Netherlands and Denmark had also made it.

The festival had begun on the Saturday with very Scottish rain. This had failed to dampen spirits, though the cold gripped the hands of pipers and drummers alike. Practising in any spare corner and even in the car park, pipes were electronically tuned and the endless carousel of bands proceeded in and out of the arena. It all appeared very Scottish but something was missing. The pipes, though stirring, fail to rouse the spirits within and seem a little devoid of the true essence of ‘Scottishness’ that hits one in the solar plexus when played with a passion that may only come with Scot’s blood.

The Sunday events seem far more relaxed. The pipe bands were far less, with the concentration today being on solo piping, and all around was a more typical Sunday morning. The games were in full flow with a range of physiques on display, from the original ‘8 stone weakling’ to the more ‘full figured’ gentleman! There seemed to be little of the classic German organisation here – perhaps as a result of a long night in the Bier Kellers hereabouts. Certainly some of the beer guts on display would seem to suggest so! ‘Putting the stone’ and carrying weights seemed to hold little interest for the crowd but ‘Tossing the caber’ was a novelty for the majority and was met with ‘oohs’ and ‘ahhs’ from the assembled throng. ‘Health and safety’ would have a field day as contestants, too close to the crowd were assisted by worried looking men rushing to the aid of those unable to shoulder the weight and staggered backwards with potentially alarming consequences!

When the ‘tug of wa’’ began the crowd was at it’s height. A team of ‘Alte Männer’ (Old men), their own title, took on all-comers and defeated even the local youth. The crowd warmed to local personalities and cheered at the ease with which their victory was won. At this moment the whole affair felt almost parochial and could indeed be a true reflection of the pride and interest that is felt with a true Scottish Highland Games.

Catching the train back to Hannover that evening allowed reflection on the weekend and all that it represented. Though it didn’t have the hills and lochs that create a backdrop to many a Scottish games, it was an echo to this in a foreign land. Those attending the Highland Gathering here in Peine showed huge enjoyment… perhaps as a novelty but an enjoyment all the same. The participants took to the event with a great seriousness and were ‘professional’ in their approach. So why did it feel so very different?

Have these places around the world simply been victims of Tartanism – picking elements of superficiality of the Scottish culture? Wrapping themselves in tartan borne of the notion of the historical/ Hollywood inaccuracy of Mel Gibson’s ‘Braveheart’ (1995). Is this something we are all guilty of? Taking those parts of any concept we like and enjoy, and using it to our own ends. The spread of such gatherings has gathered pace in recent years extending to Italy, France, Belgium, The Netherlands and Spain. Here Scottish culture is celebrated and enjoyed.

However, perhaps this should not be seen as a negative, but as a positive spread of culture that is being further developed in different ways and in different places. Would Sir Walter Scott, widely acknowledged as the originator of what we perceive of Scottish Culture today, be astounded at how it has been embraced by the world beyond? Ask any visitor here today and they too may say that for just a part of their lives, they have felt what many of us acknowledge as what makes Scots proud.

Teesdale Mercury (Barnard Castle, County Durham)

Spring 2012

Train Journeys - Middlesbrough to Saltburn

Rain-streaked windows and leaden skies herald the industrial landscape of Middlesbrough. The train screeches over sodden points and swings violently as it finds its way between industrial lines to reach the dour station. The modern amendments wrought to classic gothic architecture following Luftwaffe bombing raids of World War Two seem incongruous.

Sadly, the station mirrors the faces of those alighting and boarding the onward service to Saltburn. Greetings are cursory and passengers soon settle to the headlines and sports pages of local and national tabloids. A conversation breaks out on the opposite side of the aisle and smiles flicker in response to a shared joke but soon the silence returns.

The scene is constant – the backs of houses from pre-war terraces to modern semi-detached flaunting conservatories and well-kept gardens. These contrast with derelict factory units aired by innumerable shattered windows, burnt out cars and twisted shopping trolleys creating a seemingly post apocalyptic sculpture in a desolate wasteland. The line drags on through a despair of socio-economic decline punctuated by the jolt and shriek of brakes from the train. When spirits seem low, a line is drawn in the landscape and fields open up of swaying winter barley. The North Sea is revealed giving a sense of freedom even on the wettest of days.

Gradually there is a sense of the train slowing and grand Victorian and Edwardian townhouses rise up from the track side- the pleasant seaside resort of Saltburn is reached. Imperceptibly, the sun seems to shine and brighten illuminating the Victorian facades and welcoming the visitor. Here lies a hidden gem of the North-eastern coast, a place of escape for the workers of close by Middlesbrough.

Walking across the cliff top esplanade to the top of the gravity water fed cliff lift; the coast is laid out southwards across the beach and surf to the mass of Huntcliff at the beach terminus. The lift itself is oldest operating water-balance cliff lift in the United Kingdom and represents the ingenuity of the Victorian engineer who came up with a simple solution to a complex problem: how to get the visitor from the cliff top to the pier below.

The coast here has become the preserve of the surfer, a myriad of whom sit on boards out beyond the end of the pier awaiting the ultimate wave that will satisfy the adrenaline high craved with each visit. Car parks fill with VW camper vans adorned with stereotypical surf styled art and accompanying ‘surf dudes’. Even accents can confuse this scene for a typical Californian beach aside from the cold North Sea wind. The surf slang and gregarious behaviour stands as the furthest extreme from that observed as the train moved slowly through Middlesbrough.

Galleries, coffee shops, fish and chips, ice cream and other more typical seaside attractions abound, but it is the pure contrast between the start and end of the journey that strike the traveller.

St Cuthbert's Way: Melrose to Lindisfarne, July 2012

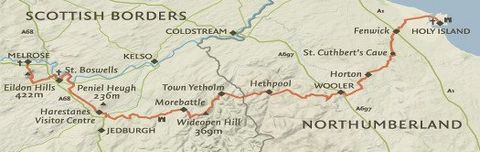

Walkers with a short period of free time will often find The Pennine Way or even The Coast to Coast too lengthy for the time allotted. St. Cuthbert’s Way will bridge this gap and give both an insight into the history of these border lands and their associated conflict and link all through the theme of the life (and indeed death) of St. Cuthbert. Designated in 1996 the route stretches 63 miles from Melrose, in Southern Scotland, to the Holy Island of Lindisfarne in North Northumberland. In the one, he began his life of religious devotion and, in the other, his life came to an end after long years of service to his God and to his fellow man.

Day One: Melrose to St Boswells to Harestanes

The delightful town of Melrose marks the start of ‘The Way’ wending the long route to the Lindisfarne. It is a wrench to leave such a relaxed place of comfort for the miles ahead, however leave I must but only after a little exploration. Famous for Melrose Abbey, resting place of the heart of Robert the Bruce found in a lead casket beneath the Chapterhouse floor in 1996. It was here that Cuthbert spent his early monastic life in an offshoot of the more important Lindisfarne Priory. Melrose at that time was in Northumbria while now residing in Scotland. It is also the birthplace of Rugby Sevens, and the rugby ground stands prominently in the centre of the town.

This morning, as the rain begins to fall steadily, is perhaps one for the numerous tea shops, but the Eildon hills beckon. These hills will stand as a landmark throughout the first two days of walking and have been occupied by ancient Britons and Romans alike that gave the three the sobriquet of Trimontium. The walk is steep and unerring in its destination. The path is slippery on red mud but eases on the crest between Mid Hill and North Hill. From here the route now descends to the quieter side of the hills where the caw of crows and the warning calls of newly fledged blackbirds ring from hedgerows.

The early onset of Autumn is noted, with sycamore and beech turning colour and shedding leaves. A feint chill is felt as the rain persists.

Bowden is reached via fields. It is a pretty little village noted for the many awards relating to Scotland in bloom, displayed in the bus shelter! The acquaintance is all too brief as the path now curls away downhill and then follows through woodland and a short minor road section to reach Newtown St. Boswells. Though the name suggests otherwise, this is not a new town at all, but simply a corrupted name arbitrarily given when the railway (closed in 1969) ran through here and the name stuck! From here the path turns downhill following a small tributary to the main river of the area – The glorious River Tweed.

The Dryburgh Suspension Bridge gives footpath access to the village of Dryburgh on an attractive meander of the river. A short walk across brings the walker to The Temple of Muses: In 1817, the 11th Earl of Buchan had erected the Temple, in the form of a Greek pavilion, as a tribute to James Thomson, the Ednam poet, who wrote the words for 'Rule Britannia'. Sitting atop Bass Hill, it once contained a statue of Apollo, the Greek God of music and poetry, but this has long gone. A local artist has designed the replacement seen today.

Crossing back over the bridge, the route now proceeds along the river to St. Boswells and to Maxton with riverside paths proving a delight. Whether at the river’s edge or above it on terraced paths there is always movement, be it from the river, an occasional leaping salmon, and oystercatchers perusing the water margins or a heron in flight.

Soon the river is left and the walk follows minor roads to the edge of the busy A68 and thence upon the Roman road of Dere Street through scattered woodland and field edges to reach a summit at Lilliard’s Edge. A stone grave marks the site of the Battle of Ancrum (1545) and reads thus:

Fair maiden Lilliard

lies under this stane

little was her stature

but muckle was her fame

upon the English loons

she laid monie thumps

and when her legs were cuttit off

she fought upon her stumps.

Standing here in such peaceful surroundings today with the sun beating down and the gentle breeze cutting a smooth series of waves through the maturing barley it seems hard to consider the bloody scenes of many a border conflict.

From here The Way descends to the woodlands of the Monteviot estate – a wonderful contrast to the open fields. Suddenly everything seems enclosed and more intimate. The solitary walker moving quietly through the woods may see roe deer or red squirrels; hear the call of the jay and endless finches; and sense the downhill towards the conclusion of the day’s walk.

Harestanes makes for a fine conclusion with its attendant facilities and those at the nearby Woodside Garden Centre (set within the old estate walled garden). A place to rest and recuperate, take stock before the most difficult section of the walk tomorrow and reflect upon the sights and sounds of the day.

Day Two: Harestanes to Morebattle to Kirk Yetholm

The rain falls steadily and drips from the vegetation as Harestanes is left. Human activity is little in evidence as the boots squelch through mud and the walk descends to the River Teviot, cutting back on itself to find a crossing. The river itself is in spate and washing high above the normal level as it races and scours the river bank. Lichens on the narrow suspension bridge make for a difficult and dangerous passage. A day of rains not only dampens the spirits but turn simple tracks into bogs and skating rinks. Walking in such conditions is far from joyful!

The route passes through extensive broad leaf woodlands, along narrow minor roads and tracks between fields of constant ups and downs. The drop and rise to and from Oxnam Water is one of the steepest. From here paths on field margins sap the spirit: overgrown after long warm and wet days- machetes at the ready! In shorts, nettles become a constant, and although the walker becomes habituated to it, more open country reveals the wounds inflicted!

From Cessford Moor the track drops down to the pretty hamlet of Cessford with its ruined castle dominating the scene. From here a laborious road walk to Morebattle begins. With little variation to alleviate the constant pounding on the feet it becomes simply a desire to reach the village and take a break.

After a short break the walk now leaves for the highlight of the day: the route over Grubbit Law and Wideopen Hill (368m/ 1207ft) is superb. Here is both the highest point of the walk and the acknowledged half way point. With the brooding Hownam Law looking down from above and the narrowing valleys stretching towards the Cheviot itself, this is a place to take stock and soak up the atmosphere. The view down the ridge to Yetholm and the undulating hills to the north add to the airy appeal of this place. The path now wends its way downwards and then along the river to end the day outside The Border Hotel. This is nominally the end (or start, depending on your perspective) of The Pennine Way and a great place to pick up some well-earned refreshment.

Day Three: Kirk Yetholm to Hethpool to Wooler

Restarting at The Border Hotel, the route stretches just over a mile along a steep purgatorial hill. Road walking for the hill walker is hard on the feet and generally devoid of interest. At Halter burn all changes - The open fells are reached and the climb to the border ridge and the actual border wall itself. This is a strange milestone: a point for celebration, as the majority of the walk is now behind tinged with a sadness to leave Scotland behind.

The descent to Elsdon Burn can be confusing when entering a wood, but retains interest throughout with soaring hills and the great whaleback of Cheviot prominent in most views. Hethpool is soon reached and the great stillness of the College Valley looms to the south. As light fails the shadows lengthen here and gradually turn through shades of blue to a deep silent black. There can be few places in Britain where a true sense of remoteness can be felt but at this moment that feeling of solitude is absolute.

With ideas of another walk on another day the route heads north once more through rough pasture to Torlees House and once again onto the open hillside – what joy! The air becomes more breathable, the soul awakes and the joy of being in such an open space is palpable.

The long ridge walk undulates over spongy turf and easy ground and, on good weather days such as this, views abound. The final drop down into Wooler follows the route of a local nature trail through the woods at Wooler Common. After a length of time spent on high ridges with views out across the Cheviots to the south, The North Sea to the east and the distant Lammermuir and Moorfoot hills of Southern Scotland, this drop into civilisation seems both welcome and strange. From here the route will no longer cross high ground but instead follow the coastal plain to the final destination.

Day Four: Wooler to Fenwick to Lindisfarne

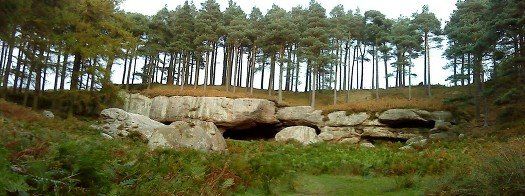

The walk from Wooler is initially uninteresting punctuated by small farmsteads, grander manor houses and rural farmlands. The walker finds himself constantly gazing over the shoulder at the fast disappearing Cheviots on the Western horizon with memories of high ridges and big skies. The rise and fall of minor roads and farm tracks is left behind at Old Hazelrigg in favour of open pasture then woodland periphery. This culminates at a stand of mature Scots Pines that lead through a broad path to the foot of St. Cuthbert’s Cave. When St. Cuthbert's remains were carried from the ruins of Lindisfarne Abbey by the clerks, they being all that remained of that religious community the others having fled, in order to bring it at that time to Chester le Street as a place of safety, they are said to have rested at this cave on their journey. St. Cuthbert's remains were later to be moved to Durham Cathedral where they still lie. This place has a truly solemn air engendering a sense of peace and tranquillity. Though stained by black smoke of countless campfires and adorned with rock-cut graffiti going back centuries (One reads 1752 – was this a place of pilgrimage for so many years?). Why is it people seem to wish to make their mark in such tranquil places, that should remain as nature intended?

As a foretaste of the sands walk to the Holy Island of Lindisfarne – this cave, named after Cuthbert, gives a sense of the devotion the monks and clerks of Lindisfarne had. Their faith to deliver the body to Chester-le-Street in County Durham is clear.

The walk downhill is typically Northumberland: craggy outcrops amidst forestry blocks and rough pasture all echoing to the lapwing and curlew under huge skies. But after Fenwick the walker is returned to reality with a sizeable bump when the A1 trunk road is encountered. Standing here for 15 minutes awaiting a safe crossing with the fumes of HGVs and countless cars makes for a desire to escape the clutches of man. Soon after the main East Coast rail line is also crossed but calm returns quickly as the distinct smell of sea air blows across the last two fields that lead down to the salt marsh that fringes the open sea. Concrete blocks built as World War Two tank traps provide a surreal sight and a prelude to the crossing over the sands on The Pilgrims’ path.

As a conclusion to a walk, this short wander across the tidal sands to the Lindisfarne Priory is perfect. As the warm sands caress the feet, sore after many miles, the thoughts are sharpened by the sea breeze and the salt air that assails the nostrils. Behind lie some 63 miles of varied walking: woodland, pasture, open moorland and, indeed, minor roads and the last few steps lead to two iconic places on the Northumberland coast – the Priory that marked Cuthbert’s ministry and Lindisfarne Castle set atop an outcropping of the volcanic Whin sill. A definite point of conclusion (The North Sea prevents us from travelling further!) – an historic end to a walk of interest historically, geographically and spiritually.

'Been There', Daily Telegraph Travel section, Torres del Paine, Southern Chile

Saturday 1st November 2003

Long considered a Summer destination, the exposed southern tip of South America is whipped by winds at all times of the year, as sailors ‘rounding the Horn’ would testify. The crowning glory of any trip to this remote area remains the National Park of Torres del Paine, an area that abounds in a range of multi national names of peaks, glaciers and lakes that indicate the history of exploration hereabouts.

Transport, by coach, minibus or taxi can be arranged in both Punta Arenas and Puerto Natales. In Summer it is also possible to sail from Puerto Natales.

The drive to the all-encompassing view of the Paine Massif along dirt roads passes typical Patagonian sheep runs amidst wild windswept hills scarred by dying trees said, in one theory, to be suffering the effects of global warming and the hole in the ozone layer above this part of the world. Condors glide effortlessly above, searching for carrion.

Once in the park, accommodation is limited in winter to a few ‘hosterias’, which remain open, such as Hosteria Lago Tyndall: a basic, yet comfortable, hotel commanding majestic views beyond the confluence of glacial rivers. Access from here takes the hotel boat and minibus to the walks that are the best way of seeing the incredible scenery and wildlife.

Roaming herds of guanacos and nandus (rheas) dot the landscape, while occasional brilliant flashes of colour are noticed as bright green parakeets flit amongst southern beech trees and pink Chilean flamingos are seen on the many small lakes.

The circuit of Paine is a Summer undertaking that circles the entire massif, but the spectacular can remain within reach of the winter walker if the weather cooperates. The three hour walk to the base of the knife like ‘torres’ (towers) leads up through a range of scenery of moor land, beech forest, then ultimately scree slope to culminate in glacial scenery and rocky moraine directly below the towers themselves. To be by oneself is to truly appreciate the grandeur of this awesome place.

Shorter walks can also leave one with a sense of awe and wonder, such as the walk alongthe shoreline of Lago Grey, where a multitude of icebergs drift up in waves at the end of their journey across the lake from Glacier Grey; or the short walk alongside Lago Pehoe to Lago Nordenskjold beneath the towering Cuernos (horns) del Paine.

In Winter it is unusual to see other tourist and far more likely that cattle ranchers drifting into the fringes of the park will be the only other humans on the tracks. If solitude in spectacular surroundings is sought then there can be few places on earth as blessed as this.